Why real-world operational results are the only valid measure of strategic intent

Strategy is often treated as a planning activity.

Execution is treated as a delivery problem.

That separation is artificial.

I learned this the hard way early in my career. We had what everyone agreed was a strong strategy. Clear positioning. Clean slides. Leadership alignment. The kind of plan that survives multiple reviews without friction.

Then it met reality.

Customers hesitated in ways we did not anticipate. Sales cycles stretched. Operations began improvising. Teams made “small” adjustments to keep things moving. Each adjustment made sense locally. Collectively, the system drifted.

The postmortem blamed execution.

It should have blamed strategy.

Because nothing was broken in delivery. The system was behaving exactly as designed. It was our assumptions that were wrong.

That was the moment it became clear that strategy does not live in decks or planning sessions. It lives in how a system behaves when incentives collide, constraints tighten, and people make tradeoffs under pressure.

In real systems, strategy does not exist independently of execution. It is revealed through it. A strategy that cannot survive operational constraints was never a strategy. It was an untested belief.

Most failures attributed to execution are actually strategy failures. The market was misread. The workflow was misunderstood. The incentives were misaligned. The system was never designed to produce the outcome leadership expected.

Execution exposes these truths early and without sentiment.

Healthcare makes this unforgiving. Regulatory friction removes optionality. Budget constraints force prioritization. Legacy systems resist abstraction. Human behavior ignores intent and follows incentives.

There is no room for theoretical degrees of freedom.

I have seen strategies that looked elegant collapse at go-to-market. Pricing models that assumed rational buyers fail under procurement reality. Products designed for “efficiency” rejected because they added cognitive load to clinicians already at capacity.

None of this was execution error.

It was strategy finally meeting the environment it claimed to understand.

Go-to-market is not downstream work. It is where strategy is stress-tested. Pricing reveals whether value is real or imagined. Adoption reveals whether the workflow actually fits into daily operations. Retention reveals whether the outcome mattered enough to change behavior.

When leaders treat these signals as delivery noise, they miss the lesson. When they treat them as strategic feedback, they gain clarity fast.

The strongest operators I know stopped defending ideas early in their careers. Not because they lacked conviction, but because they learned that conviction without validation is fragile.

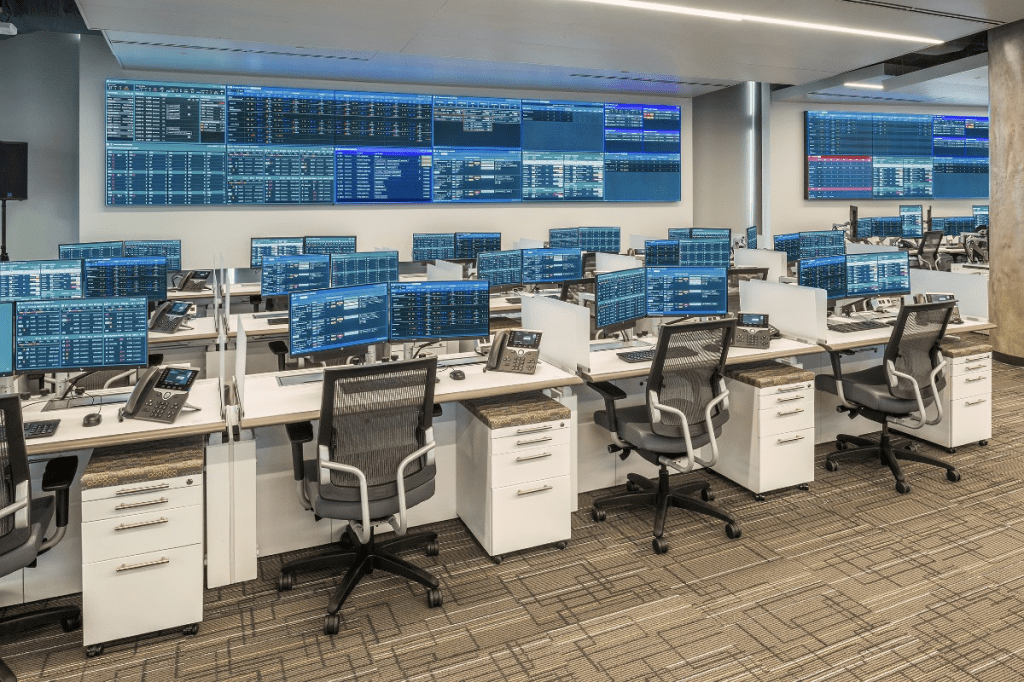

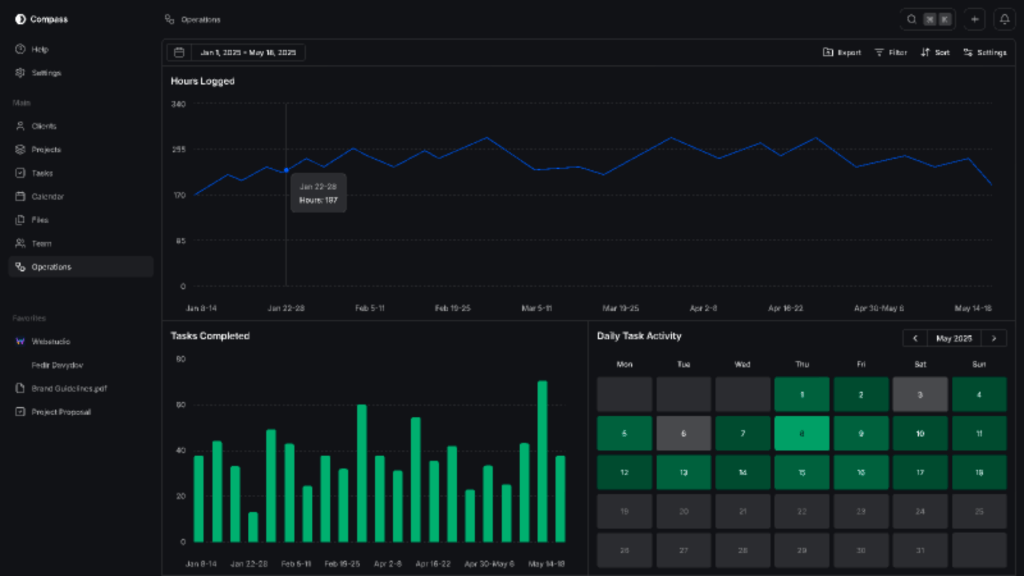

They instrument reality instead.

They watch how the system responds. Where friction accumulates. Where people bypass the design. Where workarounds appear. They assume the system is telling the truth, even when it contradicts intent.

Then they adjust structure, not narrative.

This is why effective leaders do not separate strategic thinking from operational design. They build strategies that already contain execution logic. They ask different questions upfront.

Who absorbs the cost of this decision?

Where does this slow someone down?

What happens when volume doubles?

What breaks first?

These are not tactical questions. They are strategic ones.

When results diverge from intent, strong leaders do not act surprised. Surprise is a sign of distance from the system. They diagnose instead. They treat outcomes as data, not judgment.

Execution is not where strategy ends.

It is where strategy finally becomes real.

And if the system cannot produce the outcome without heroics, intensity, or constant intervention, the strategy is incomplete.

That is not a delivery problem.

That is the strategy telling the truth.